Tawau, the east Malaysian district where Christina Ak Lang grew up, is a tropical paradise. The surrounding sea is a brilliant blue, so clear you can see the coral reefs below. Journeying inland, you’ll find gently rolling hills covered with thick stands of trees.

It was in one of these forests that Lang spent many happy days in her youth. “The forest was my playground,” the 43-year-old says. “I used to see sun bears and wild boars.”

But now, much of Tawau’s terrain has been transformed. The rain forest where Lang played is gone, replaced like many others in the area by rows of spiky palm trees that stretch as far as the eye can see. These are the oil palm plantations that today cover more than 50% of the landscape.

“I feel sad that it’s all turned into oil palms,” says Lang, an office supervisor at Sawit Kinabalu, the third-largest oil palm grower in the state of Sabah, where Tawau is found. (Oil palm is the name of the plant; palm oil, its product.) But, she says, “plantations can help increase people’s standard of living.”

For developing countries like Malaysia that are trying to grow their economies, the oil known as “liquid gold” holds special promise. Around the world, from Guatemala to Gabon, tropical rain forests are being replaced by plantations growing the orange-red fruits from which palm oil is extracted. Today oil palms cover almost 67 million acres—an area larger than New Zealand.

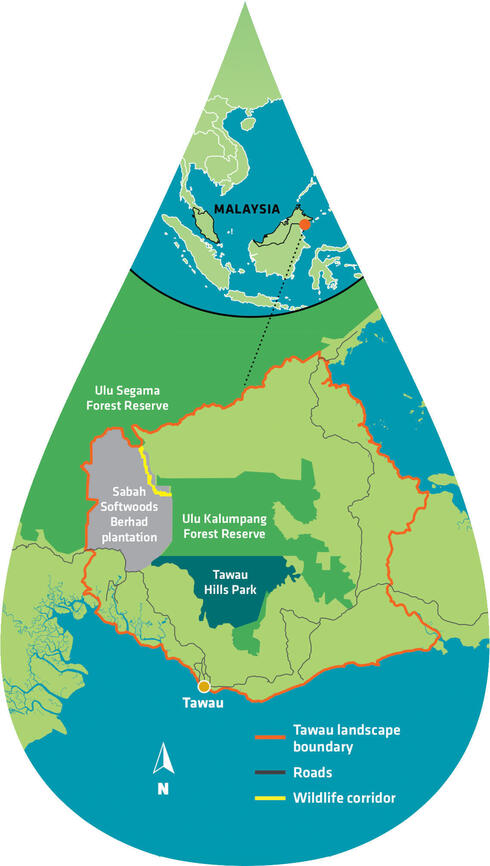

“It’s a fundamental driver of deforestation,” says Glyn Davies, WWF-Malaysia senior advisor. “Borneo—the world’s third-largest island, comprising the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak, as well as Brunei and five Indonesian provinces—has lost 47% of its forest to palm oil in the past 20 years.”

“A fifth of Sabah,” Davies continues, “is now covered by a single crop, where wildlife-rich forests stood 40 years before.” And as forests have been cleared, animals like the sun bears and wild boars that Lang used to see have been robbed of their habitats.

But today Sabah is aiming to change this trajectory. Primed by local civil society, the state government has committed to meeting the highest standards for responsible palm oil production by 2025 using a pioneering “jurisdictional approach”—one that looks beyond individual plantations and strives for sustainability goals across the whole state. And WWF-Malaysia’s Living Landscapes program is contributing to this by bringing together diverse stakeholders in the key landscapes of Tawau, Lower Sugut, and Tabin; testing innovative approaches; and informing the statewide effort in the process.