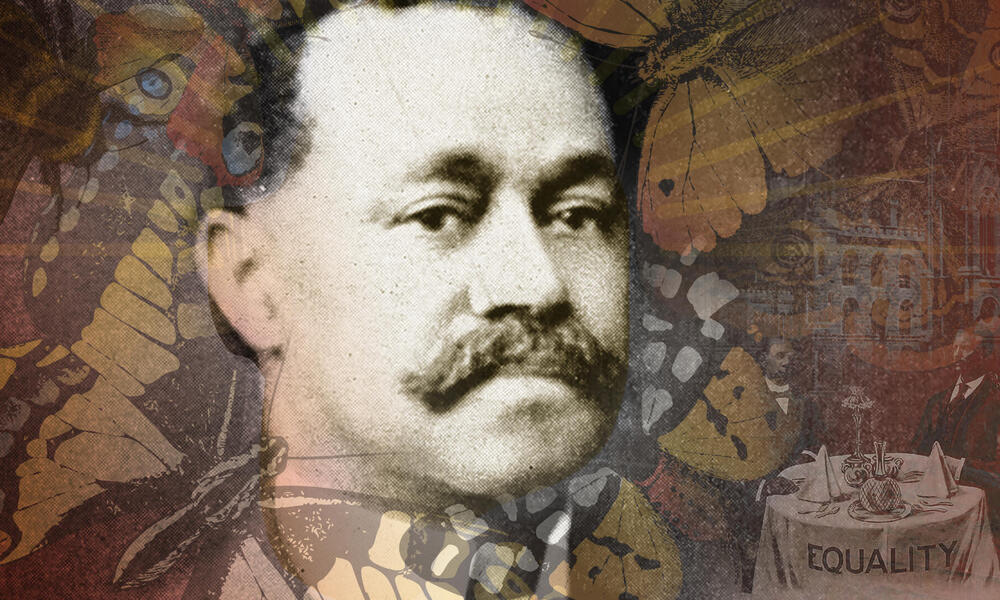

Abundantly curious and clever, during his lengthy career he discovered several behavioral characteristics that are taken for granted today. We know that insects can hear and that honey bees see color and recognize patterns because of Turner's work. He also delved into much less conventional territory by studying Pavlovian responses in insects, along with navigation, and courtship behavior in solitary bees. His investigations were truly groundbreaking and novel. By the time of his untimely death in 1923 at the age of 56, he had published more than 71 research papers.

With such admirable accomplishments, one can easily imagine a storied career within one of the world's great scientific institutions. However, tragically and despite his brilliance, Turner wasn't afforded this opportunity. Instead, he diligently worked as a high-school science teacher to make ends meet. Although other unknown factors may have played a part, to historians it is apparent that he was disqualified from loftier appointments solely because of his race. One can only imagine the frustration and hurt that he must have felt by such blatant discrimination.

The authors of a 2009 paper wrote that prior to the entomologist's career insects were viewed as primitive creatures, reacting only instinctively to external stimuli, without any other remarkable capacity. For example, as early as 1907 Turner proposed that ants are much more than mere reflex machines; they are self-acting creatures guided by memories of past individual experience. This is a sentiment well and truly ahead of its time. I can't help but wonder if some part of Turner's desire to shed light on their worth was driven by a longing to see his own value recognized by society.

When I spend time observing bees in the grasslands of the Northern Great Plains, one of the things that I notice most often is how intelligently they behave. They fly from flower to flower with purpose, selectively choosing one flower over another. My understanding of bee intelligence and the value of these insects to the ecosystem has long been informed by the brilliance of Charles Henry Turner. What's tragic is that I didn't even know this until 2021 when I first learned of him. While we can't ever really right the many wrongs of the past, we can consciously acknowledge and lift those exceptional individuals whose dedication to learning more about life on our Earth had been unjustly relegated to the dustbin of history simply due to the color of their skin.

Charles Henry Turner, thank you for your brilliance and unceasing dedication to learning more about our insect friends. I wish that I could have known you sooner.

If you’d like to learn more about Charles Henry Turner, these papers (1 and 2), offer a great overview of his life and career. There is also a children’s book called Buzzing with Questions: The Inquisitive Mind of Charles Henry Turner.